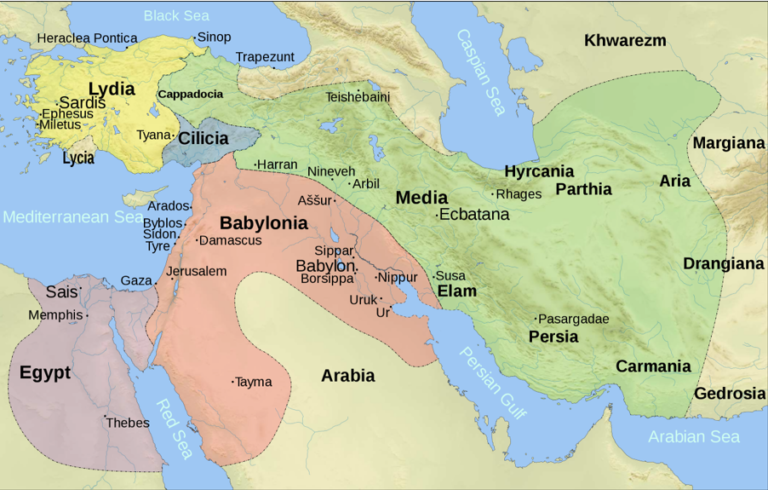

Numerous archaeological sites [1] in the Hamadan area have been unearthed, although research into these findings has been limited. Nonetheless, it has been determined that these relics trace their origins back to the pre-Achaemenid era. Among these sites, there have been discoveries of rectangular bricks, which notably deviate from the square blocks typically attributed to the Achaemenian period. The broader region boasts several significant archaeological sites, including Baba-Jan and Surkh Dam in Lorestan, as well as Ziwa and ‘Zindani Suleiman’ in Kurdistan. At the Baba-jan site, an intriguing structure has been uncovered, featuring a third layer that appears to have experienced fire damage, along with an additional layer that appears to have enveloped it. This site shares striking similarities in its architectural elements and layers of materials with ‘Noshi Jan’ and ‘Godin,’ suggesting that the historical presence of the Medes empire may have extended across these regions during the respective historical epochs.

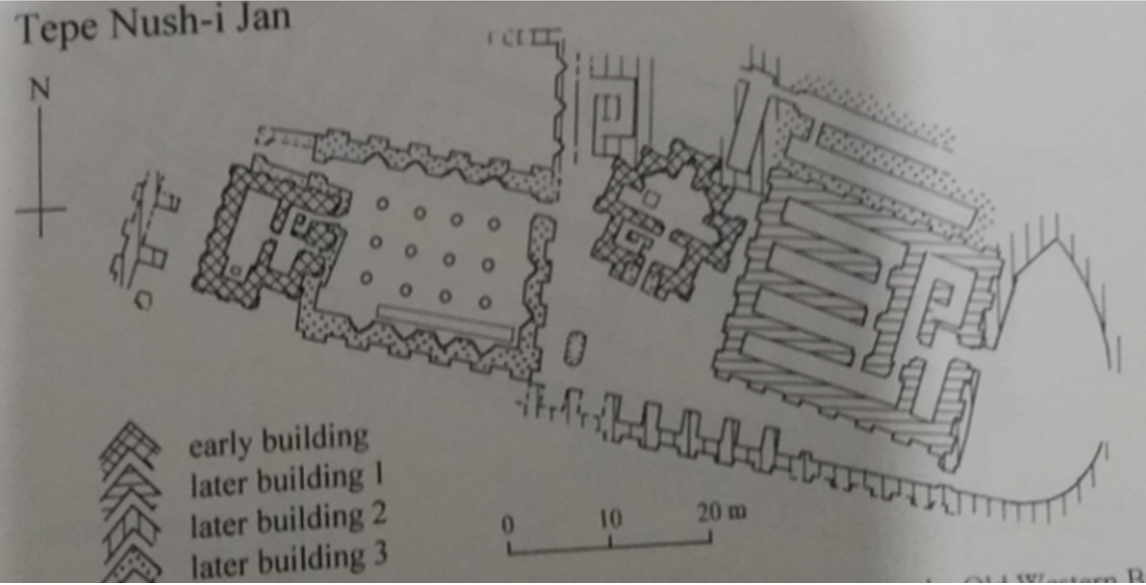

Noshi-Jan, located 70 kilometers southeast of Hamadan, is regarded as a sacred site, housing a temple situated atop a hill. This sacred place is believed to have been constructed using four or five types of clay bricks. The temple’s central feature is a fire temple, marked by the presence of a central fireplace. Remarkably, the temple’s walls are adorned with intricate carvings and drawings. Similar architectural characteristics can be observed in ancient sites like Persepolis, Dahani Gulaman, Kushi Khawaja, Qumis, and even Taljamish in Palestine.

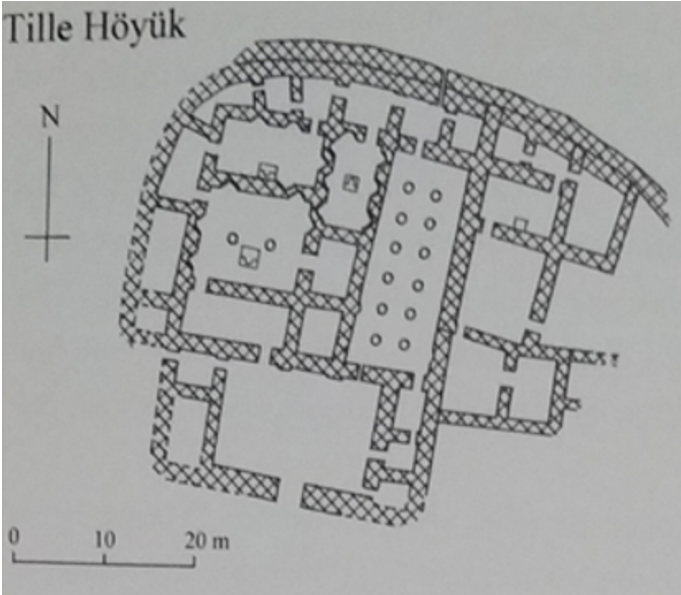

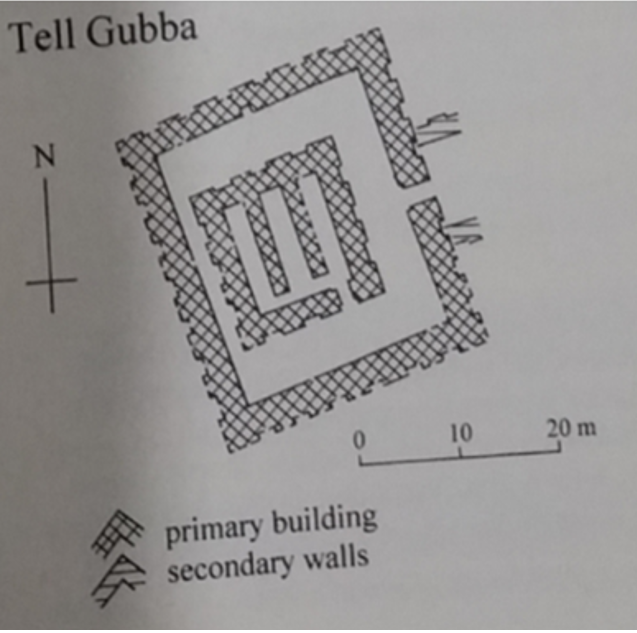

Another intriguing site is ‘Gudin Tepa,’ a religious site associated with the Medes. This site exhibits parallels with two other historical sites: one known as ‘Til Guba’ in Iraq and the other referred to as ‘Til Huyuk’ in Turkey.

My Examination

Firstly:

The archaeological knowledge pertaining to the Medes has often been considered somewhat restricted, which poses challenges in locating and excavating sites containing artifacts and relics. While these findings offer substantial evidence of the Medes’ existence, it is disheartening to note that many of these valuable relics have been intentionally vandalized, set ablaze, and possibly pilfered, primarily by sworn adversaries of the Kurdish people. These artifacts and relics are often disassociated from the Medes’ historical context and attributed instead to the foreign heritage of Iraq or Iran, finding their place in museums. This attribution to Achaemenid rule disregards the substantial influence the Medes had on Old Persian culture, encompassing aspects such as clothing and adornments. In essence, why should we not directly link these artifacts to the Medes themselves?

Unfortunately, a considerable number of Mede artifacts fell prey to looting, especially following the Kurdish uprising in 1991. The looted artifacts were a consequence of neighbouring nations exploiting the chaos. Reports suggest that Iran was involved in the illicit export of artifacts, leading to extensive looting of monuments in southern Kurdistan. The fate of these looted artifacts remains uncertain, as they might have been destroyed or clandestinely circulated in the antiquities market. It is conceivable that some of these artifacts are presently on display in museums, inaccurately labelled as Persian heritage.

Secondly:

The scholarly research focused on the archaeology of Median sites seems to lack an objective perspective, possibly influenced by Persian viewpoints. For instance, Michael draws attention to two noteworthy archaeological sites situated in close proximity to Hamadan: ‘Tap-Noshi-Jan’ and the ‘Godin-Tap’ area. The excavations conducted at these sites have unearthed clay pots dating back to the 7th or 6th centuries BCE, marking the final phase of the Iron Age within the three-age classification. Interestingly, Michael points out that although there are resemblances in the ceramic types discovered at sites like Baba-Jan and Surkh Dam in Lorestan, as well as Ziwa and ‘Zindani Suleiman’ in Kurdistan, they are located beyond the boundaries typically associated with the Medes. However, other sites dating to the 6th century BCE, unquestionably falling within the historical period of the Medes, exhibit notable parallels. This raises the pertinent question: if there are similarities between these two archaeological sites, and the time gap is not substantial, why should we not consider both sites as integral parts of the Median historical record?

—

Note:

[1] Curtis, Later Mesopotamia and Iran, 62-66.