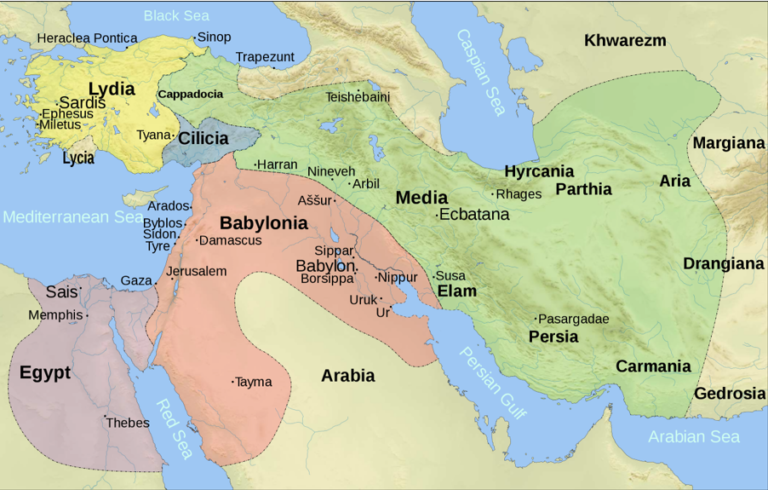

To address this inquiry comprehensively, it is imperative to delve into a historical period characterized by the decline of the Ottoman Empire. During this era, individuals were routinely bought and sold as slaves and servants in various marketplaces. However, it is noteworthy that the concept of slavery or the slave trade was not prevalent in Kurdistan due to the deep cultural heritage and adherence to Zoroastrianism among the Kurdish population The tenets of this faith fundamentally oppose the idea of enslaving individuals, considering such actions as morally unacceptable. Consequently, Kurdish society has fostered a cultural ethos of treating all races equitably, and this norm has become deeply ingrained in their traditions.

In the past, several nations exploited the trade in slaves and servants as a profitable enterprise to amass substantial wealth within the territories under their control. These nations encompassed the Arabs, Turks, and certain European powers. The practice of enslaving men and women from conquered regions is universally regarded as a brutal and inhumane act. Nevertheless, the Kurdish people steadfastly rejected the practice of slavery and resisted subjugation by dominant nations. Despite their adversaries’ attempts to enslave them, the Kurds steadfastly refused to surrender without a fight. They were willing to risk their lives in battle rather than endure the indignity of being sold as part of slave caravans or subjected to punishment through spiked slave collars.

Throughout history, the enemies of the Kurds endeavoured to enslave them but were thwarted due to the Kurds’ unwavering resistance and refusal to yield. Consequently, these adversaries resorted to deceitful tactics, such as plotting conspiracies to sow discord among Kurdish leaders for personal gain or to preserve their own power. These duplicitous and malevolent practices were driven by the enemies’ desire to weaken Kurdish society and undermine its political influence. The inability to enslave the Kurds posed a significant challenge to their adversaries, who had to resort to covert and nefarious means to achieve their objectives.

For instance, during the British occupation of Iraq during World War I, during which none of the Kurdish tribes were compelled to join British forces and become casualties of war. Following the British victory, they did not take any individuals as slaves, distinguishing their actions from their practices in Africa and India.

The Kurdish heritage is emblematic of a commitment to liberating people from tyranny, exemplified by figures such as Saladin, who emancipated slaves and vowed not to harm those who surrendered during wartime.

In Baghdad, the institution of slavery persisted until the demise of the Ottoman Empire. Moreover, individuals belonging to different religious faiths were susceptible to being targeted in such transactions. In the 1840s, the Scottish traveller James Frazer visited Baghdad and documented his observations in his journals. He observed that only Muslims were legally permitted to own slaves, rendering them the sole group capable of thriving economically in the city. This restriction extended to Christians, Jews, and practitioners of other religions, irrespective of their social status. Non-Muslims were also prohibited from riding animals on the streets of Baghdad. During King Dawood’s rule, these individuals were even prohibited from riding horses or mules, while during the Caliphate of Ali, there was greater leniency toward non-Muslims in this regard.[1]

Kurdish adversaries have frequently employed conspiratorial policies in their attempts to subjugate the Kurdish population. Unfortunately, these conspiracies have often met with success, sometimes facilitated by internal betrayals that the Kurds have found challenging to combat. Nevertheless, the Kurdish people have consistently striven to eradicate such injustices and have remained resolute in the face of formidable adversaries. While they have launched numerous rebellions in pursuit of their liberation, a definitive victory remains elusive.

—-

Note:

[1] Fraser, 277.